When large structures are built inside of cells, how are their dimensions determined? Are cues received that tell the structure to keep growing, or to slow down, or to stop growing altogether? A recent study published in Developmental Cell by a team led by Molecular and Cell Biology PhD student Melissa Chesarone-Cataldo and Professor of Biology Bruce Goode begins to address these questions by focusing on cytoskeletal structures called yeast actin cables.

Actin cables serve as essential railways for myosin-dependent transport of vesicles, organelles and other cargo, required for yeast cells to grow asymmetrically and produce a daughter cell. Cables are assembled at one end of the mother cell and run the length of the entire cell, but no longer, or else they would hit the back of the cell, buckle and misdirect transport. So how does an actin cable know how long to grow? How are other properties of the cable, such as its thickness and mechanical rigidity determined, and how important are these properties for cable function in vivo?

Actin cables are assembled at the bud neck by the formin protein Bnr1, and rapidly extend into the mother cell at a rate of 0.5-1 µm/s. At this speed, the tip of the actin cable reaches the back end of the cell in about 5-10 seconds. Each cable consists of many shorter overlapping pieces (individual actin filaments) that are stitched or cross-linked together to form a single cable, and cables continuously stream out of the bud neck due to the robust actin assembly activity of Bnr1. Chesarone-Cataldo et al. asked the question, “what mechanism prevents the cables from colliding with the back of the cell and overgrowing?” In doing so, they identified a novel actin cable ‘length sensing’ feedback loop, dependent on the myosin-passenger protein Smy1.

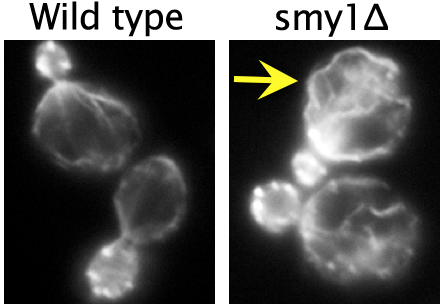

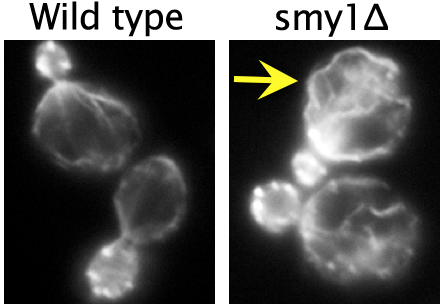

Using live-cell imaging, they showed that Smy1 molecules are transported by myosin from the mother cell to the bud neck, where they pause to interact with the formin Bnr1. Purified Smy1 attenuated Bnr1 activity by slowing down the rate of actin filament elongation. When the SMY1 gene was deleted, cables grew too long, hit the rear of the cell and buckled (see image, right). In addition, the mutant cables abnormally fluctuated in thickness and were kinked, impairing transport of myosin and its cargoes.

Using live-cell imaging, they showed that Smy1 molecules are transported by myosin from the mother cell to the bud neck, where they pause to interact with the formin Bnr1. Purified Smy1 attenuated Bnr1 activity by slowing down the rate of actin filament elongation. When the SMY1 gene was deleted, cables grew too long, hit the rear of the cell and buckled (see image, right). In addition, the mutant cables abnormally fluctuated in thickness and were kinked, impairing transport of myosin and its cargoes.

The authors propose that a negative feedback loop controls actin cable length. In their model, the cargo (Smy1 in this case) communicates with the machinery that is making the cable (the formin Bnr1), as a means of sensing ‘railway’ length. The longer the railway grows, the more passengers it picks up, and the more transient inhibitory pulses the formin receives. As such, longer cables are selectively attenuated, while shorter cables are allowed to grow rapidly. This negative feedback loop allows yeast cells to tailor actin cable length to the dimensions of the cell and to the needs of its myosin-based transport system.

Current work in the Goode lab is aimed at testing many of the mechanistic predictions of the model above and understanding how Smy1 functions in coordination with other known regulators of Bnr1, all simultaneously present in a cell, to produce actin cables with proper architecture and function. In addition, experiments are underway to find out whether related mechanisms are used to control formins in mammalian cells and to understand the physiological consequences of disrupting those mechanisms.

Chesarone-Cataldo M, Guérin C, Yu JH, Wedlich-Söldner R, Blanchoin L, Goode BL. The Myosin passenger protein Smy1 controls actin cable structure and dynamics by acting as a formin damper. Dev Cell. 2011 Aug 16;21(2):217-30.