Michael Rosbash, the Peter Gruber Endowed Chair in Neuroscience and Professor of Biology and his wife, Nadja Abovich, established the Rosbash-Abovich Award as a way to inspire and acknowledge excellence in research by post-doctoral fellows and graduate students in the Brandeis life sciences. The Rosbash-Abovich award will be awarded annually.

The award honors the most outstanding papers published the previous year that have been authored by a Brandeis postdoctoral fellow and a Brandeis PhD student. In addition to the honor being selected, each winner is presented with a monetary award.

Future winners will present their talks at upcoming Volen Scientific Retreats, but due to COVID restrictions, the 2020 winners will be presenting their talks during the Molecular Genetics Journal Club meetings.

Most outstanding paper by a post-doctoral fellow

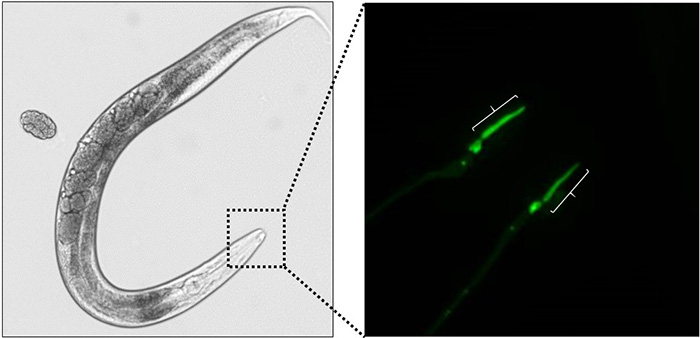

The 2020 winner for the most outstanding post-doctoral paper is Michael O’Donnell for the publication titled “A neurotransmitter produced by gut bacteria modulates host sensory behavior“. O’Donnell, is a former postdoc in the Piali Sengupta Lab. Sengupta said

Mike is a remarkable scientist and mentor. He single-handedly and independently established a new research direction in my lab. He also served as an informal mentor to many graduate students and has continued to do so even after he left my lab. I greatly appreciated our long discussions and arguments, and he is very much missed.

Sengupta also noted that O’Donnell was chosen to receive this award

on the basis of the creativity and novelty of his work that was published in Nature. The committee was particularly interested in nominating a researcher who was a driving force behind the work and Mike certainly fulfilled this criteria.

O’Donnell is now an assistant professor at Yale and recently formed the O’Donnell lab. He presented his talk to the Molecular Genetics Journal Club on December 2, 2020. He spoke about his work on neuromodulators produced by different bacteria.

Most outstanding paper by a PhD student

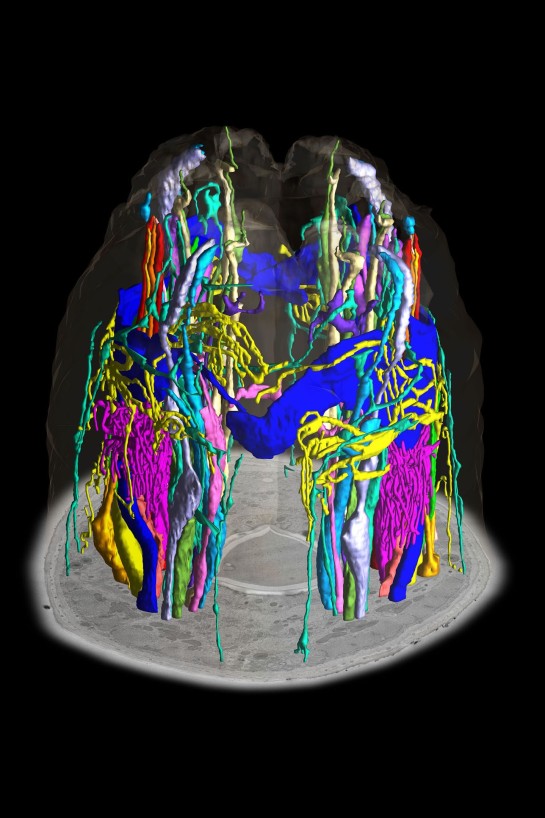

The recipient of the 2020 award for the most outstanding PhD student paper is Gonen Memisoglu for the publication “Mec1 ATR Autophosphorylation and Ddc2 ATRIP Phosphorylation Regulates DNA Damage Checkpoint Signaling.“ She was a PhD student in James Haber’s lab. She received her PhD in 2018 and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Chicago. She will be presenting her talk at the Molecular Genetics Journal Club on February 2, 2021.

When asked about his former PhD student, Haber said

I was delighted to learn that Gonen was the recipient of the Rosbash/Abovich award for the best publication by a graduate student last year; but I had to ask “which paper” because Gonen made two important discoveries last year about the way cells respond to DNA damage. Gonen helped develop a highly efficient way to edit the yeast genome and to create dozens of very precise mutations in the Mec1 gene that is the master regulator of the DNA damage response. When there is a chromosome break, the Mec1 protein phosphorylates a number of proteins that creates a cascade of signaling to prevent cells from progressing through mitosis until damage is repaired. Gonen discovered that the extinction of the this signal depended on Mec1’s autophosphorylation of one specific target and that changing that specific amino acid to one that could not be phosphorylated was enough to cause cells to remain arrested. She also identified several alterations of the Ddc2 protein that associates with Mec1 that were also critical for its normal activation.

During her time in my lab Gonen was a super hard-working and exceptionally insightful grad student, but also incredibly generous with her time, helping others in the lab