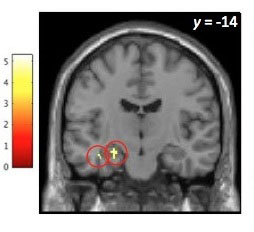

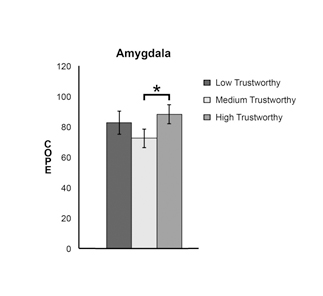

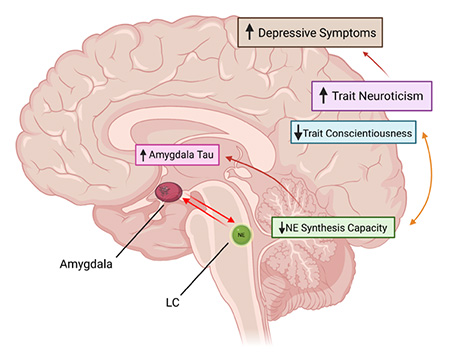

More than 6 million people in the U.S. are living with Alzheimer’s disease in 2022. The prevalence of this neurodegenerative disease has prompted scientists to study the factors that may increase someone’s risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Higher neuroticism is a well-known dementia risk factor, which is associated with disordered stress responses. The locus coeruleus, a small catecholamine-producing nucleus in the brainstem, is activated during stressful experiences. The locus coeruleus is a centerpiece of developing models of the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease as it is the first brain region to develop abnormal tau protein, a hallmark feature of the disease. Chronic activation of stress pathways involving the locus coeruleus and amygdala may promote tau spread, even in cognitively normal older adults. This leads to the question of whether high-neuroticism individuals show non-optimal affective function, altered locus coeruleus neurotransmitter function, and greater tau accumulation. Researchers in the Neurochemistry and Cognition Lab, led by Dr. Anne Berry set out to answer this question. PhD candidate Jourdan Parent examined relationships among personality traits, locus coeruleus catecholamine neurotransmitter function, and tau burden using positron emission tomography imaging in cognitively normal older adults. She found that lower locus coeruleus catecholamine function was associated with higher neuroticism, more depressive symptoms, and higher tau burden in the amygdala, a brain region implicated in stress and emotional responses. Exploratory analyses revealed similar associations with low trait conscientiousness, a personality trait that is also considered a risk factor for dementia. Path analyses revealed that high neuroticism and low conscientiousness were linked to greater amygdala tau burden through their mutual association with low locus coeruleus catecholamine function. Together, these findings reveal locus coeruleus catecholamine function is a promising marker of affective health and pathology burden in aging, and that this may be a candidate neurobiological mechanism for the effect of personality on increased vulnerability to dementia.

PhD candidate Jourdan Parent examined relationships among personality traits, locus coeruleus catecholamine neurotransmitter function, and tau burden using positron emission tomography imaging in cognitively normal older adults. She found that lower locus coeruleus catecholamine function was associated with higher neuroticism, more depressive symptoms, and higher tau burden in the amygdala, a brain region implicated in stress and emotional responses. Exploratory analyses revealed similar associations with low trait conscientiousness, a personality trait that is also considered a risk factor for dementia. Path analyses revealed that high neuroticism and low conscientiousness were linked to greater amygdala tau burden through their mutual association with low locus coeruleus catecholamine function. Together, these findings reveal locus coeruleus catecholamine function is a promising marker of affective health and pathology burden in aging, and that this may be a candidate neurobiological mechanism for the effect of personality on increased vulnerability to dementia.

Locus coeruleus catecholamines link neuroticism and vulnerability to tau pathology in aging. Jourdan H.Parent, Claire J.Ciampa, Theresa M. Harrison, Jenna N. Adams, Kailin Zhuang, Matthew J.Betts, Anne Maass, Joseph R. Winer, William J. Jagust, Anne S. Berry. NeuroImage, 30 September 2022, 119658.