Seen at the Gelles Lab Little Engine Shop blog this week, commentary on a new paper in Nature Communications, published in collaboration with the Goode Lab and researchers from New England Biolabs.

“Single-molecule visualization of a formin-capping protein ‘decision complex’ at the actin filament barbed end”

[ensemblevideo contentid=Z33TDbsofEW7ofOXsSti8w autoplay=true showcaptions=true]

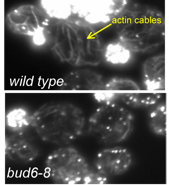

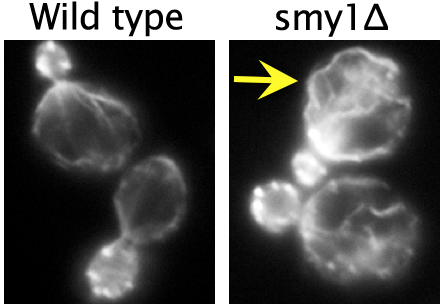

Regulation of actin filament length is a central process by which eukaryotic cells control the shape, architecture, and dynamics of their actin networks. This regulation plays a fundamental role in cell motility, morphogenesis, and a host of processes specific to particular cell types. This paper by recently graduated [Biophysics and Structural Biology] Ph.D. student Jeffrey Bombardier and collaborators resolves the long-standing mystery of how formins and capping protein work in concert and antagonistically to control actin filament length. Bombardier used the CoSMoS multi-wavelength single-molecule fluorescence microscopy technique to to discover and characterize a novel tripartite complex formed by a formin, capping protein, and the actin filament barbed end. Quantitative analysis of the kinetic mechanism showed that this complex is the essential intermediate and decision point in converting a growing formin-bound filament into a static capping protein-bound filament, and the reverse. Interestingly, the authors show that “mDia1 displaced from the barbed end by CP can randomly slide along the filament and later return to the barbed end to re-form the complex.” The results define the essential features of the molecular mechanism of filament length regulation by formin and capping protein; this mechanism predicts several new ways by which cells are likely to couple upstream regulatory inputs to filament length control.

Single-molecule visualization of a formin-capping protein ‘decision complex’ at the actin filament barbed end

Jeffrey P. Bombardier, Julian A. Eskin, Richa Jaiswal, Ivan R. Corrêa, Jr., Ming-Qun Xu, Bruce L. Goode, and Jeff Gelles

Nature Communications 6:8707 (2015)The capping protein expression plasmid described in this article is available from Addgene.

Readers interested in this subject should also see a related article by Shekhar et al published simultaneously in the same journal. We are grateful to the authors of that article for coordinating submission so that the two articles were published together.